Co-authored by Rida Morwa.

When I was young, I became obsessed with magic. While many might enjoy watching the theatrics of a magic show, my mind was always on how everything was done. I would record David Copperfield and watch, rewind, watch, rewind until the video was worn out. I was always trying to figure out the “secret” of the magic trick. I’d go to the library and read books about magic tricks, and take what I learned there to deduce how various performers tricked the mind.

It turns out, that many magic tricks have their basis in math. Those who create magic tricks use their knowledge of math, science, and psychology to devise illusions that create an entertaining show.

Today, I am going to perform a magic trick, which has its basis in math. While the trick probably isn’t going to get me an invitation to replace Criss Angel, it does provide great insight into how we should think about our investment portfolios and how we withdraw cash from them.

Dividends “Don’t Matter”?

Some have developed the theory that “dividends don’t matter”, and that an investor could achieve the same effect by selling off shares as they need cash. Their reasoning is that cash paid in dividends are paid from the company, and therefore the value of the company is reduced by the exact amount of the dividend.

Indeed, cash paid from the company is not available for other uses. The book value of a company is reduced by the exact amount of the dividend with each payment.

So what is the one detail that this theory is missing out on?

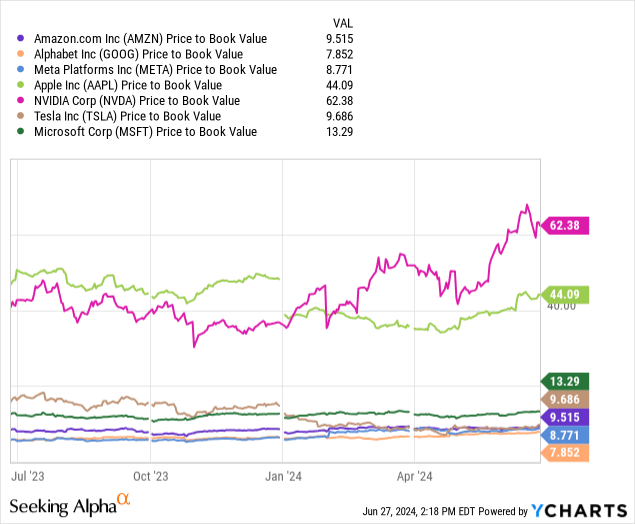

The reality is that the stock market does not value companies based on book value. That’s a good thing for the “Magnificent 7” as they trade at enormous premiums to book value:

Alphabet (GOOG) (GOOGL) trades at the smallest premium of “just” 785%. It would only have to fall 83% to trade at book value. NVIDIA (NVDA) trades at the largest premium to book value and would have to fall over 98% to reach book value.

I’ll go out on a limb and suggest that these kinds of collapses among these companies aren’t likely to happen. While one might argue that certain types of companies are likely to trade closer to book value, even those that some suggest “should” trade at book value often don’t.

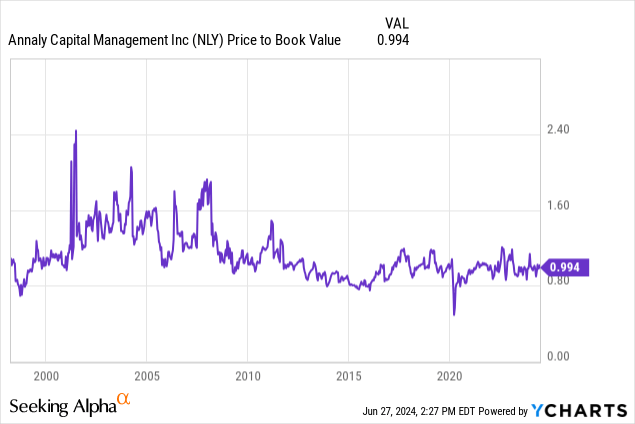

For example, Annaly Capital (NLY) is a mortgage REIT that invests primarily in agency mortgage-backed securities. Agency MBS is a very liquid asset, that you can buy directly through your brokerage account. As a result, many suggest that book value should be the prime measure of valuation.

Historically, NLY has traded from 80% to 160% of book value.

Since stock prices aren’t directly tied to book value, $1/share paid in dividends could be worth more or less than $1 in share price movement. Share prices move every day, the value of a dividend in your pocket doesn’t.

This isn’t always a meaningful distinction. If you are in a bullish stock market and prices are always going up, then selling shares can result is very similar cash flows as a stock with identical returns that pays a dividend. If shares are trading at large premiums, then $1/share on the balance sheet might generate far more than $1/share in share price.

However, when a bear market happens, and everything in the market is trading at a significant discount, receiving a dividend or selling shares can be the difference between you destroying your portfolio and coasting through the bear market. This is due to “Sequence of returns” risk.

The Magic Of Sequence Of Returns

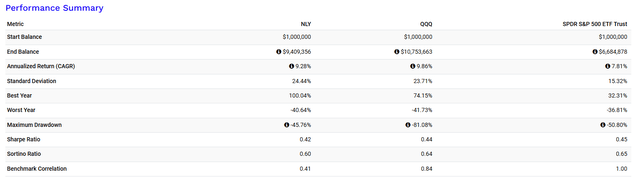

I’m going to show you a magic trick. Here is a chart of Annaly Capital (NLY) compared to Invesco QQQ Trust (QQQ) and the S&P 500 from April 1999 through June 26, 2024:

Portfolio Visualizer

On a $1,000,000 original investment, QQQ more than doubled in the following year before the dot-com bubble burst, causing it to underperform. From 2002 through 2024, QQQ caught back up and outperformed NLY.

Portfolio Visualizer

So if you could go back in a time machine and had to choose one of these holdings to buy and hold no matter what, QQQ would be your choice, right? After all, it ends with an extra $1.3 million in value. Who doesn’t want an extra $1.3 million?

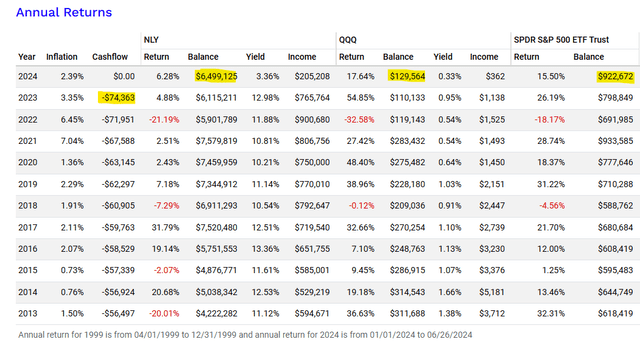

Now for the magic trick. The same time period, the same tickers, with one small change. You see, the investor with $1 million in 1999 likely felt very good about retiring. $1 million is still a good bit of money today, but in 1999? If you were a millionaire, people thought you were set for life. So if that investor retired, and started withdrawing $40,000/year indexed to inflation (AKA “the 4% rule”), here is what that looks like:

Portfolio Visualizer

NLY goes from slightly underperforming, to dramatically outperforming. The investor in QQQ, using the 4% withdrawal rule, has to be extremely concerned. They have $129,564 left from the original $1 million, and the 4% rule prescribes withdrawing over $75,000 in 2024. Something that clearly could not be done safely. Meanwhile, the NLY investor has $6.5 million in share value, income of over $765,000 in 2023 and is withdrawing less than 10% of the income to meet the target withdrawal.

Portfolio Visualizer

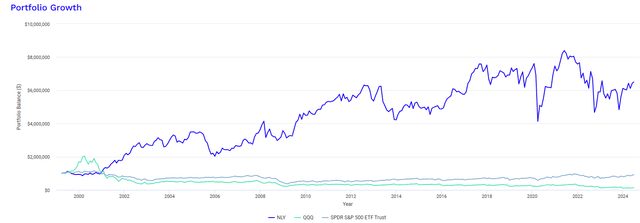

How can such a relatively small withdrawal cause such an enormous difference? Let’s go back to where the wheels came off and look at the annual returns in the early years:

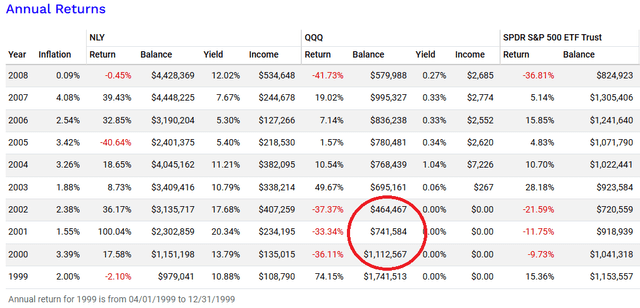

Pay attention to the value of QQQ in 2000 through 2001 without withdrawals:

Portfolio Visualizer

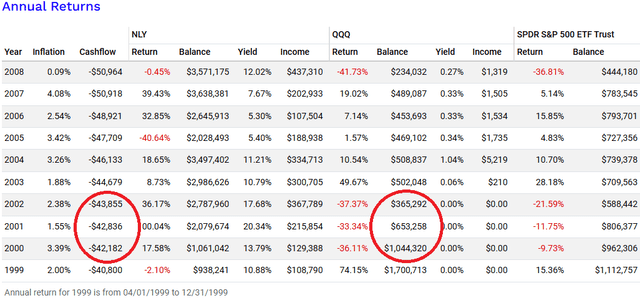

Now compare the same numbers with cash being withdrawn:

Portfolio Visualizer

The withdrawals caused the QQQ position to be worth 21.5% less by 2002, than it would have been if the funds stayed invested. In essence, the investor was forced to sell shares at poor prices. So by 2007, without withdrawals, QQQ was able to fully recover and survive the Great Financial Crisis. With withdrawals, it was only able to recover to $489k and in 2008 it was at $234k while withdrawals were approaching $51k. Forcing the selling of even more shares at low prices.

Tell me again how “selling shares is no different than dividends”.

Selling Low Destroys Capital

It’s math. If you are selling shares at low prices, then when the price recovers you will hold fewer shares, and therefore it will take more upside to get you back to even. With an income approach, where the amount of dividends you receive is greater than your withdrawals, you are buying more shares when prices are low.

The fastest way to devastate your retirement portfolio is to be forced to sell when prices are low. The Income Method is a strategy designed to avoid ever being forced to sell shares to withdraw income. This way, you can decide to sell on your own time, at good prices.

Note that dividend investments are not magic. They do not guarantee that you will get a particular dividend indefinitely. They can perform exceptionally well, or poorly. Dividends can be cut, raised, or even suspended. Also, if you withdraw more cash than is produced by your dividends, you may be forced to sell shares at poor prices, creating the same problem QQQ had above.

A well-constructed income investment strategy incorporates these risks. This is why we recommend having a diversified portfolio of at least 42 income-producing investments, rather than all your investments in a single ticker. We recommend an allocation to fixed-income, which tends to be more stable. Finally, we suggest planning on reinvesting at least 25% of your dividend income, both to provide a source of income growth and also to provide a buffer in the event that we see a period of higher than average dividend cuts.

What Dividends Are Not

Dividends are not “magic money” conjured out of thin air. They are payments paid by a company or fund to shareholders. Those payments come from cash that the company or fund acquires. Where does the company or fund get that cash? It can vary. It can vary for the same company across different payments.

- Cash on hand: Sometimes a company might have excess cash sitting on their balance sheet.

- Operating cash flow: Many companies will pay dividends from the cash that is generated by their operations. Various non-GAAP metrics often aim to measure the amount of recurring cash flow being produced by the company’s operations. These include FFO (Funds From Operations), AFFO (Adjusted Funds From Operations), FAD (Funds Available for Distribution), and CAD (Cash Available for Distribution). These metrics can often be a fantastic way to estimate the sustainability of a dividend. However, be aware that even if the metric carries the same name, the calculation may vary from company to company. It is essential that you look at the reconciliation to GAAP earnings so that you understand what adjustments have been made. If comparing two different companies, make your own adjustments so that the metrics are comparable.

- Investment Income: Some businesses primarily make money through investments. Mortgage REITs or BDCs are examples of companies that generate most of their earnings through investments.

- Capital gains: Capital gains can be sources of cash that is eventually distributed. In many cases, large capital gains are a source of one-time “special” dividends. However, for other investments, it might be a recurring part of their strategy. For example, CEFs (closed-end funds) are required to distribute most of their realized capital gains. So if you invest in a CEF, you can expect a significant portion of your dividends to stem from capital gains.

- Borrowing: A company might borrow money, usually on its revolver, to fund a dividend payment.

- Raising capital: Companies can raise cash from issuing common or preferred equity.

When evaluating a dividend-paying investment, it is critical that we take the time to understand the business model of the company and where its dividends are going to be paid from.

Obviously, we want to avoid companies that are funding their dividends primarily through temporary or unsustainable sources like borrowing, unless we have a very clear picture for how they will achieve coverage in the future.

There is no shortcut. Using a metric to screen investments to narrow down the number of options you want to do a deep dive on can be helpful. However, you cannot rely on headline metrics to tell you how a dividend is being paid and whether or not it is safe. There are always numerous things going on within a company. They might be increasing their overall debt level to expand, but the dividend is comfortably covered by existing operations. Or a company might have significant capital gains that won’t be recurring, making the dividend appear covered when it won’t be in the long run.

Conclusion

Dividends aren’t magic, but they are capable of performing a very incredible magic trick. They can prevent you from being forced to sell shares during a market downturn. Share prices are volatile, and they can often have very little to do with the underlying business. For those of us who are not forced to sell shares, the volatility of share prices is an advantage. We get to choose on any particular day whether we want to be a buyer or a seller.

For those who are forced to sell shares, the volatility of market prices is a great risk. Selling shares at poor prices is the greatest threat to a retirement portfolio. Unfortunately, it is something that many find themselves doing out of fear or necessity.

An income-based strategy can help deal with some of the complications created by volatile prices. We have a tangible measure of what we are getting paid. Just like with your job, you know exactly how much you got paid. Live on less.

I’m not going to tell you I have the secret code to avoid losses. Life isn’t a video game, there is no cheat code. Anyone who tells you they have a way to guarantee you make $X without a risk of loss, buyer beware.

What I will tell you, is that if you take time to approach the market in a reasoned and logical manner, it can be a great generator of wealth for you. You will need to keep a level head, avoid panicking, and work to identify the best investment options for your goals.

Focus on what the companies do, and how they generate cash to pay the dividend. Make your best estimate as to whether or not they will be able to continue to do that. Sometimes you might be wrong, and that is ok.

Focus on building your income, and make sure you are withdrawing less. Maintain a cushion of excess dividends, and if that cushion shrinks, that is a warning sign for you to change things in your portfolio. The greatest benefit of an income strategy is that you are not faced with the decision that so many had to make in 2001/2002 on whether or not it was safe to withdraw funds. Since you aren’t spending money until it is paid to you, you know the budget you have to work with, and you know if you need to do something to either increase your income or reduce your spending before it is too late.

More often than not, investors who take an income approach to the market will be surprised at just how much income their portfolio is capable of producing. They often get to enjoy the magical feeling that comes with having a lot of cash flow.

Read the full article here