A recession is on the way.

I become more persuaded of that every day.

My view could change, of course, if the data changes and if trends reverse. But right now, with near uniformity, the trends in the economy seem to point toward an ensuing recession. And I cannot see what, at this point, would catalyze a reverse in those trends.

I’ll lay out my reasoning below, stringing together a menagerie of charts to make my case, and you can decide for yourself.

Afterward, I’ll explain how I’ve positioned my portfolio for huge dividend growth both during and after a potentially ensuing recession.

This article is on the longer side, but I think (and hope) it will be highly valuable to you in thinking through your own investment decisions if I am right that the US economy is on the verge of recession.

Where, O Interest Rates, Are Thy Sting?

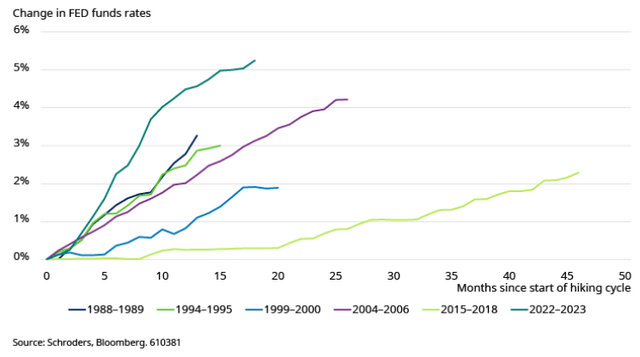

Longtime market observers know that virtually every sustained Federal Reserve rate-hiking cycle has ended with a recession, partially as a result of rising interest rates.

Generally speaking, the sharper the increase in rates, the quicker the recession ensues.

And the current rate-hiking regime has been the sharpest and harshest in 40 years.

Schroders

Of course, the Fed’s rate hikes were in response to the sharpest spike in inflation in 40 years, but due to lags in the government’s inflation metrics, the Fed was late to the party and felt compelled to hike far faster than usual.

As it turns out, real-time inflation peaked and began turning down midway through their hiking cycle, and that trend continues to today. But since the Fed is looking at old data, they persist in their tilt toward tightening.

Where is the pain from the Fed’s monetary tightening showing up?

Some look at charts like this and conclude that the long-term debt corporations took out during the era of ultra-low interest rates makes the private sector insulated from rising rates.

Deutsche Bank

But this chart is heavily impacted by a handful of corporate giants that are the size of some small developed countries. The market cap of Apple (AAPL), for example, is larger than the entire economy of France, which boasts the 7th largest GDP in the world.

These mega-caps are cash-rich and have very little debt, meaning that the interest they earn on their cash is often greater than the interest they pay on their debt.

The effective interest rate for the top 10% of the S&P 1500 remains below 2.5% today, whereas for the bottom 50% of public companies, it has surged to over 5.5%.

Bloomberg

This is a reminder that Wall Street does not equal Main Street, and market cap does not equal economic value.

If you compare, for example, the S&P 500 (SPY) to the equally weighted S&P 500 (RSP), you’ll find that the latter is down this year even as the former is up over 14%!

That is due almost entirely the “Magnificent 7” mega-cap stocks that dominate the cap-weighted index.

In fact, a chart comparing the YTD price performances of the Vanguard Mega Cap ETF (MGC) to the Vanguard Small-Cap ETF (VB) shows almost the exact same pattern.

If you want to see where interest rates are biting or where the recession will start (is starting?), you can’t simply look at the SPY. You have to look elsewhere.

Weakness Under The Surface

Recessions are like predators. Just like nature’s predators, the economic predator that is recession always targets the weakest prey first.

The crippled zebra is the first to get eaten by the lion. The kangaroo joey that falls out of its mother’s pouch is the one that gets carried off by the dingoes. The lone seal, separated from its pod, is the one that gets targeted by orcas.

Nature is red in tooth and claw, and the economy is no less merciless an ecosystem. Recessions always come for the weakest prey first, then progressively make their way toward stronger economic actors.

Consumers

Financial media often talks about “the American consumer” as if everyone is equal to the average. That is inaccurate. There is wide variation from high-income to low-income, from plenty of savings to zero savings, from zero debt and passive investment income to lots of personal debt and income only from a part-time job or Social Security.

During and for a while after COVID-19, this variation in consumers was masked by the massive fiscal stimulus that shielded households from the negative effects of social distancing and lockdowns.

Enhanced unemployment benefits and economic impact payments (aka “stimmy checks”) caused a massive bubble in excess savings, which has been steadily depleting since the summer months of 2021.

JP Morgan

Today, the “excess savings” that has acted as the primary driver of inflation, economic activity, and job growth in the aftermath of COVID-19 appears to be exhausted.

Consumers’ steady deployment of this excess savings into the economy is the primary reason why the US economy did not enter recession in 2023, despite many calls for recession amid rapidly rising interest rates.

“But what about wage growth?” you ask.

During the pandemic and for a while afterward, many households were cash-rich enough to not need to rush back into the labor market. Unemployment benefits were still flowing, parents were still monitoring their kids’ online schooling at home, and recently retired Baby Boomers still felt fine about their financial situation.

So, the mismatch between cash-rich consumers and an undersupply of available labor caused wage growth to spike, peaking at a 6.6% 3-month annualized rate in the Spring of 2022.

Bloomberg

But today, more workers have come back into the labor market (easing the undersupply issue), while consumers are being forced to rein in spending due to depleted savings (easing the excess demand issue). Thus, job and wage growth are both slowing.

There does not appear to be any signs of a brewing wage-price spiral.

In fact, it’s important to realize that, even after the wage growth of the last few years, nearly all growth in real (inflation-adjusted) disposable personal income per capita since COVID-19 began came from government stimulus spending.

YCharts, Modified by Author

The government pushed trillions of newly printed dollars into the economy in 2020 and 2021, which explains the huge spikes in disposable household income during these years. But since the end of this stimulus spending, real disposable income per capita has been basically flat.

Zooming in to the last two years, we find that from Fall 2021 through Summer 2022, real personal incomes fell as inflation surged. Then real incomes bounced back for the next year as wages caught up with inflation.

YCharts, Modified by Author

And now, real income seems to be on another downward slide, this time because of a cooling labor market and falling wage growth rather than high inflation.

And yes, despite very low unemployment, the labor market is cooling.

The quits rate (percentage of employed people quitting their jobs) is back to its pre-pandemic level. This is important, because the biggest driver of wage growth over the last several years came from job switchers.

Bloomberg

Meanwhile, the pace of hiring is below 2019 levels, and while job openings officially remain above pre-pandemic levels, this is probably inflated due to multiple listings for the same position (a byproduct of remote work).

For two years now, the trend in net job growth has been downward.

Torsten Slok

At its present course, net job growth will be negative by late Spring / early Summer 2024.

Not even the Yuletide joy of the Christmas season seems capable of reviving the labor market. This October’s seasonal retail hiring was the lowest since 2018 and slightly below the long-term average, perhaps pointing to a further slowing in consumer spending.

Torsten Slok

Approximately 70% of US GDP comes from consumption, so a cooling labor market, falling wage growth, and depleted savings obviously weigh heavily on economic growth.

But it gets worse.

Slightly over 60% of Americans say they live paycheck-to-paycheck. It is clear that a growing number of these households are running a deficit each month, funding the gap between income and spending with debt.

Hence we find that credit card debt is shooting to new all-time highs, and delinquency rates are spiking as well.

I show the delinquency rate, because the standard way to disregard soaring credit card debt is to say “GDP and personal incomes have gone up too, and therefore rising credit card debt isn’t a problem.”

But surely such a sharp spike in credit card delinquencies is a problem!

About 2% of credit card borrowers went into delinquency in the most recent quarter, the highest percentage since the Great Financial Crisis.

New York Fed

More and more Americans are being forced to cut back on spending by falling behind on their credit card balances. This can go on for a little while, as consumers find ways to shift and consolidate their debt. But it can’t go on forever.

If wages were growing fast enough, many credit card balances could gradually be paid off, thus preserving borrowers’ ability to spend on credit. But wages have not kept pace with debt levels.

Since Summer 2021, credit card debt has risen 3x faster than nominal disposable personal income.

And, given that interest rates on credit card debt are among the highest of any type of debt in the economy (20%+), it’s not surprising to see that non-mortgage personal interest payments are soaring at their fastest level on record, both as an absolute level and as a percentage of disposable income.

Bloomberg

As a share of income, personal interest payments may not yet by at their highest level over the last 40 years, but look at the trend. By the end of this year, that metric should crest the high reached in the mid-2000s. By mid-Spring 2024, it should reach a new 40-year high.

This doesn’t just come from credit cards.

Recent Fitch data shows that used car loan interest rates for subprime borrowers has risen as high as ~21%, and the percentage of subprime borrowers at least 60 days delinquent on their car payments is at its highest level since 1994.

Recall the point about recessions being predators attacking the weakest prey first. Almost by necessity, the bulk of this personal debt is concentrated among the 60%+ of Americans living paycheck-to-paycheck.

The weakest consumers are the first to see their spending drop, but they won’t be the last.

Businesses

Consumer spending is business revenue, so as consumers gradually pull back, we should see that show up in private sector financial performance.

Sure enough, mentions of “weak demand” have spiked recently on conference calls, reaching a higher level even than during the GFC of 2008-2009.

Bloomberg

In the same vein, we find this business survey from Evercore ISI, where company executives are asked about the present state of their business. In 2021, at the height of pandemic stimulus, businesses reported an “overheating” environment matched only by the dot-com bubble era of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Evercore ISI

Since then, self-reported business conditions have plummeted from “strong” to “solid” to “struggling” in the span of two years.

For context, the current reading is right around the level at which the survey average stood as the US economy entered recession in 2001 and late 2007.

This year, bankruptcies are on pace to reach 2020 levels, which would make 2023 virtually tied for the highest number of bankruptcies since the GFC.

S&P Global Market Intelligence

And consider that this year, unlike 2020, the US economy has not been in recession! At least, not an officially declared one. Not yet. (That could change with the benefit of hindsight, as data is refined and revised.)

Recall the chart at the beginning of the article showing how smaller publicly traded companies have much higher effective interest rates. This is higher still for privately held small businesses.

Small businesses account for 40-50% of GDP and around the same share of total employment in the US. As the pinch of higher interest rates increasingly takes effect, expect to see more bankruptcies and layoffs from small business.

Just as for consumers, recessions prey on the weakest businesses first, not the cash-rich mega-caps.

My All-Weather Portfolio Strategy

Regular readers know that my financial goal is to build the largest, safest, and fastest growing passive income stream possible.

But putting those three adjectives together into a real portfolio isn’t as easy as it sounds.

- “Safest” basically just means quality businesses

- “Largest” means higher yielding stocks over lower yielding stocks and therefore a value tilt — or, “quality at a reasonable price”

- “Fastest growing” means both regular dividend increases and reinvestment of dividends

My basic approach to portfolio construction, as outlined in “How I’m Building A Monster Dividend Portfolio,” is to think of my portfolio like a Medieval galley ship.

In this framework, a dividend portfolio has three basic segments:

| Rowers | Steady, reliable compounders |

| Ballast | High-quality dividend growth ETFs |

| Sails | Higher risk stocks expected to generate higher yields on cost |

The ballast makes up only 12% of my portfolio, split across four ETFs:

- Schwab US Dividend Equity ETF (SCHD)

- iShares Core High Dividend ETF (HDV)

- WisdomTree US Quality Dividend Growth ETF (DGRW)

- Global X MLP & Energy Infrastructure ETF (MLPX)

The point of these four ETFs is to collectively make a solid ballast for my portfolio, providing a foundation of wide diversification and strong quality.

All four ETFs target quality in their stock-picking methodologies in their own unique ways. SCHD looks for high return on equity and low leverage.

DGRW does the same while adding a growth factor to tilt toward faster growers.

HDV screens first for quality and financial health, including Morningstar’s economic moat rating system, and then picks the 75 highest yielding names.

Lastly, MLPX ends up with a higher quality midstream energy portfolio simply by owning only the largest companies in this industry, whether structured as MLPs or C-corps, and excluding the smallest companies that tend to be higher leveraged.

But the biggest and most important segment is the rowers.

The core constituents of my portfolio are strong, high-quality, defensive compounders that keep growing steadily regardless of market or macro conditions. They are akin to the rowers on a Medieval galley ship. Those oars propel the ship forward whether the wind is favorable or not.

All 8 of the high-quality REITs I pitched in “Buy REITs Before Everyone Else Does” are “rowers.”

There are three basic reasons why I’m overweight REITs in my portfolio:

- My professional background is in real estate, and this industry is my wheelhouse.

- My ballast ETFs have almost zero exposure to real estate.

- The real estate business model is highly conducive to safe, steadily compounding cash flows and dividends.

But there are other, non-REIT businesses that also make great “rowers,” such as:

| Non-REIT Types of Rowers | Example |

| Temporarily Discounted Blue-Chips | Diageo (DEO), down ~20% YTD due to temporary sales softness and a guidance cut |

| Renewable Power Producers | Clearway Energy (CWEN, CWEN.A), down over 30% YTD due to interest rates, despite zero refinancing risks until 2028 |

| Multi-Decade Dividend Growers | Medtronic (MDT), down ~10% YTD on (misguided) concerns about the impact of GLP-1 drugs |

Meanwhile, the “sails” are those higher-risk portfolio holdings that either sport high dividend yields or high dividend growth rates. When the winds are favorable, these holdings should contribute powerfully to my portfolio’s dividend income. But unfavorable winds can make them a hindrance.

Last week, I explained in “A Fleeting Opportunity To Upgrade Your Dividend Portfolio Quality” when and why I sold Medical Properties Trust (MPW), a hospital REIT that has crashed recently on a combination of tenant and refinancing worries.

MPW was a “sail” holding for me. I sold it at over 3x its current price of $4.24, but even that involved a big loss on my cost basis. Fortunately, I became aware of the major issues facing MPW early this year and sold in advance of the dividend cut.

This loss demonstrates how these “sail” holdings don’t always work out to my portfolio’s benefit.

On the other hand, another “sail” holding has been Hercules Capital (HTGC), an internally managed business development company specializing in VC-backed growth-stage companies.

With the two primary tailwinds of aging demographics increasing demand for pharmaceuticals and artificial intelligence increasing software opportunities, HTGC’s growth trajectory has only improved in recent years, even amid higher interest rates. That, on top of its excellent underwriting and floating rate loan book, have propelled the BDC to incredible total returns since I first began buying it roughly 5 years ago.

I consider this three-segment portfolio construction an “all-weather” strategy. Not that the constituents never change, but the structure of the portfolio stays the same in any economic environment.

Bottom Line

My fundamental approach to investing is built on one simple principle:

Owning an equity stake in a business is inherently a long-term endeavor and should be treated as such.

Any money I may need in the next few years remains in cash or some fixed-income asset with an appropriate maturity date.

Having cash sufficient for emergencies or to sustain you through a layoff is invaluable for peace of mind. And money earmarked for near-future purchases is of course best suited for money markets or bonds with appropriate maturity dates.

But investing is inherently a long-term endeavor of unknown and unknowable holding periods. You can’t (or, at least, shouldn’t) determine in advance exactly how long you’ll hold the investment. Investing requires flexibility, patience, and prudence.

Therefore, the trite saying is true: Time in the market is better than trying to time the market.

I believe a recession is coming, and what I am doing differently because of it?

Answer: Nothing.

One investment criterion I have for any holding is the belief that it will be able to sustain its dividend through recessions. I try not to own the smaller, weaker companies most likely to fall prey to the predator of recession.

If anything, the only modification I’ve made in my investing today has been to keep a more watchful eye on my “sails” while doubling down on the most opportunistic “rowers.”

With that strategy, I believe my portfolio will continue to generate monster dividend growth, regardless where the economy goes.

Read the full article here